I had contacted Brittany American Cemetery

ahead of the trip and received a lovely email from the Assistant Superintendent, Alan Amelinckx, saying that he would pick me up at the Hotel Altos

and drive me to St. James (about 19 kilometres/12 miles) and back on the day of my visit.

Alan showed up promptly and to my surprise was

an American who worked for the American Battle Monuments Commission and had come to St. James with his family for a tour of duty. He is a delightful

young man, and had lived in France as a child so the job seemed like a natural for him. He is also steeped in this history and even wrote his thesis

on the war.

Alan Amelinckx

We stopped in the village of St. James so I could buy flowers. It's a tiny little French town oozing charm on a beautiful Spring day. Alan's kindness and friendliness lessened my apprehension and I realized I was enjoying myself. I even felt a little guilty about that. I realized at that point that I didn't know what I was supposed to feel.

The Brittany American Cemetery is, to put it inadequately, gorgeous. Manicured and perfectly maintained, I'd wager it holds its own compared to any anywhere. The beauty of the place astonished me.

We stopped at the office where I was introduced to Gerald Arseneault, the Superintendent. Alan picked up a bucket of sand gathered from Omaha Beach which he explained would be used to make the engraving in the cross-marker legible, since the all-white marble is difficult to read otherwise. Then he and I proceeded through the grounds to find my father.

This beautiful statue is engraved:

I have fought a good fight

I have finished my course

I have kept the faith

All of my earlier lightheartedness disappeared as we moved through the cemetery and I was caught up in a cloud of reverance. There was no doubt that we were treading on hallowed ground and bird song among the newly flowering trees was the only sound as we walked on the soft grassy paths.

You cannot help but be swept into emotional tumult by the sight of the numbers of crosses -- those thousands of young, dead boys -- and this is only one cemetery. There are many others, Normandy, Ardennes, Chapelle, for World War II, and then many more for World War I. It flattens your heart to think of the pain and loss that this vista of white marble represents.

When we found my father, there was already a charming bouquet of flowers and a flag on his grave. I questioned Alan who explained that a member of Brest 44, a French organization devoted to keeping alive the memory of their liberators, had visited and put the flowers there in honor of my visit. I later found out that this man was named Regis Jan, and I would soon meet him. I added my lilies to the tribute.

Regis Jan - Brest 44

Alan offered to take a picture. It seemed wrong somehow. I was not an accidental tourist on holiday. But another part of my brain said, 'you'll forget this and you want to remember. Do it to hold onto the memory." So I said yes. My body language bespeaks my discomfort.

Alan asked if it would be okay if the sound system (located in the chapel) played taps for my dad, and I said yes of course. The loud speaker system carries the music across the fields of crosses, and it is a haunting and beautiful 'day is done' experience.

Then Alan left me alone to be with my dad. He said he'd wait in the chapel and that I could take all the time I needed.

I stood at my father's grave and waited to see what would come. I'd imagined this moment from the instant that I found out where he was, but I had no idea what my own private reaction would be. Would we "talk?" Would I confess my life and loss to him? Would I forgive him for leaving me? I stood there and waited. But nothing came. In a very slow dawning, I realized that I did not feel his spirit present. His bones may have been under my feet, but his spirit was not there. He had not come to this place with his body parts. I reeled in the realization. There was no one there for me to talk to except myself.

This is not to say that my emotions were not running amok. While I shed only a few tears, I felt like I was grieving for an entire world of millions of wives, mothers, sons and daughters of soldiers. You couldn't behold these crosses without going beyond your own private losses to the bigger picture. The enormity of it all was overwhelming.

As I walked up the path to the chapel, my mind kept hopping to the question of my own doubts. Why was I not having the experience I expected? Was I capable of feeling my own feelings? Was I capable of even being "inside" my own experience at the time that I experience it? These questions and more bombarded me and at the same time, I felt that I could have wept for every buried boy and his family if I dared unleash the flood gates of my grief.

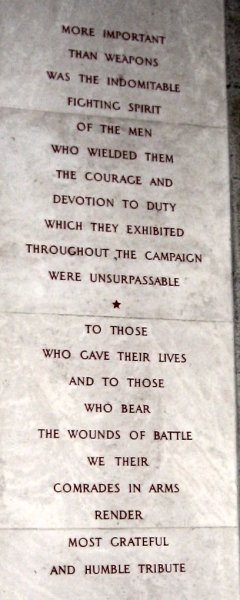

I knew I was bitter about war. All my life I had been against the wars of my generation, Vietnam, Korea, Iraq. But this war, THIS Second World War was truly a war worth fighting--and there was no denying that the sacrifices had impacted the entire world. My father would have understood that. All these boys knew what they were up against. It was certainly my duty to honor them by the way I lived my own life in the freedom that had protected. This was a very soothing thought.

As I approached the chapel, I was glad that I had brought something of significance away from this place. I was not disappointed. My journey was not over. And I had not ever given enough thought to the gift we were all given by these brave, young men.

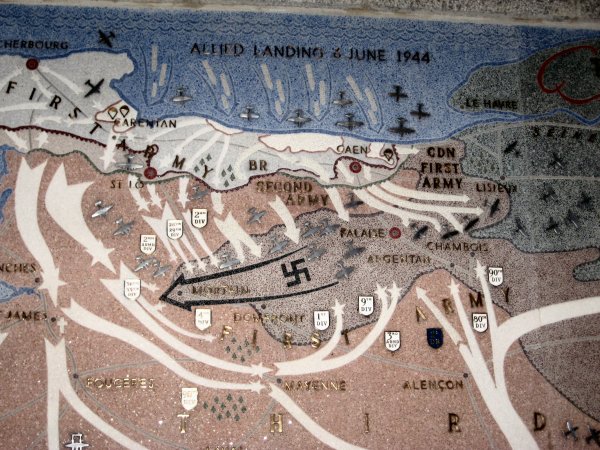

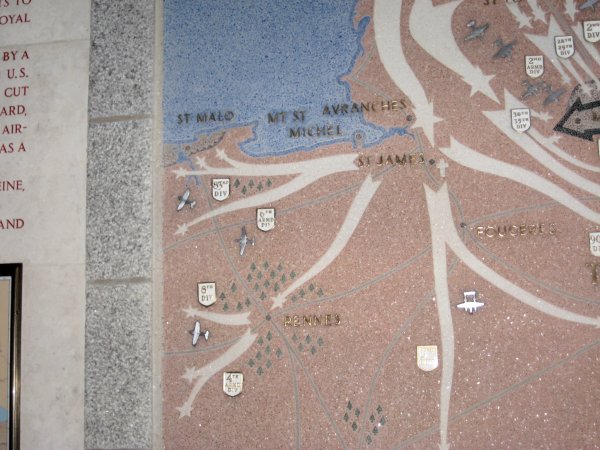

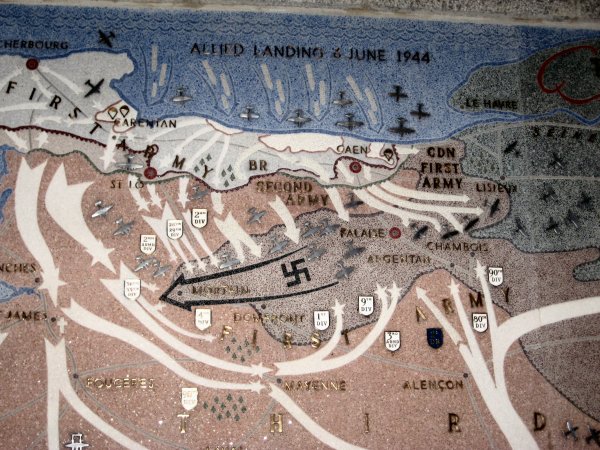

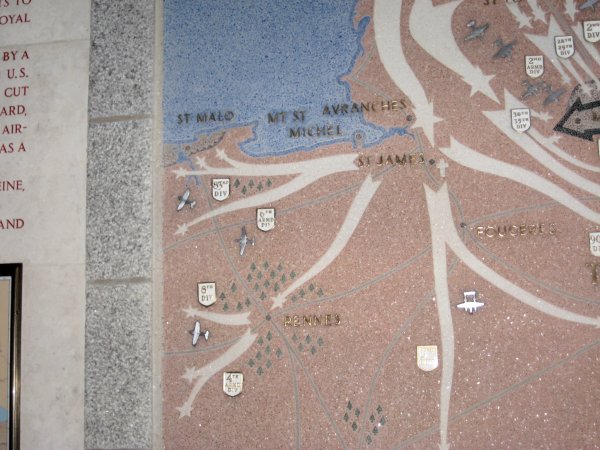

The walls of the chapel carried incredible maps of the war, and how the Nazis were surrounded and stopped in France. Looking at those maps and the familiar names of those battlefields and landing sites made my skin goosebump. The 1940's became all too real again. Germany had occupied this nation and had to be stopped.

On this map, West of St. James, closer to St. Malo was where my father's plane fell. In a little village called Saint Vougay. Maybe, I thought, there would be more answers for me there.

The chapel was very beautiful. If I was a religious person, I might have stopped to pray. There was certainly every reason to do so in this place. And I think, in fact, in some informal and internal way I did. I prayed for peace.

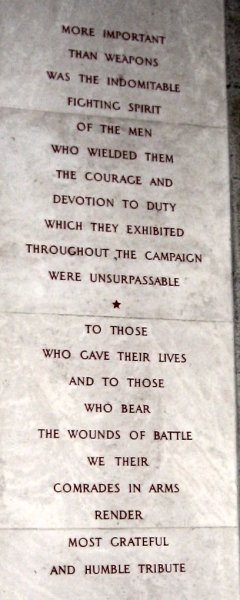

The words of Churchill and Roosevelt are carved into the chapel walls

After reading the walls, Alan and I ascended the chapel steps to the bell tower. From the tower, the whole of the cemetery spread below us.

The peace and beauty of this place was undeniable. I felt a weight lift as we stood flag high above the grounds and surveyed the exquisite memorial to our boys. It had done them proud and I was glad to have seen it.

<

Alan had been a fine friend, guide and source of knowledge and history for me, and I am thankful for his attentive and compassionate treatment while I visited. It made a big difference to have that support with me, traveling alone. I want him to know how grateful I am.

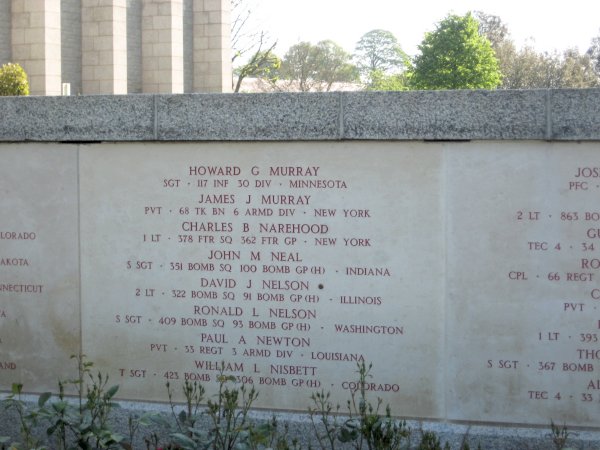

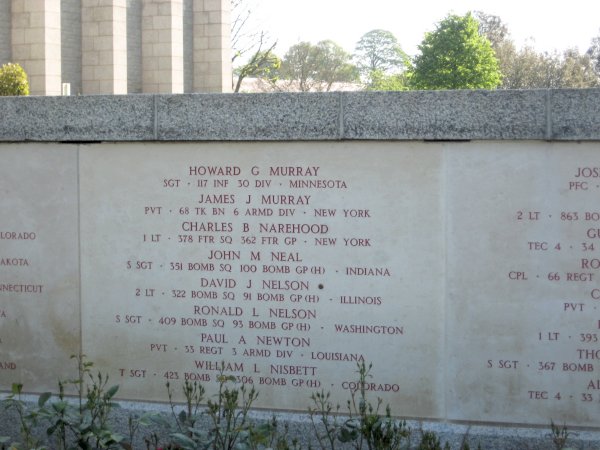

As we left the chapel, we passed a wall of names which Alan explained were the names of those missing soldiers never found, and not yet buried here. Where there was an asterisk next to the name, it meant that the remains

had later been found and were now interred here. The wall was long...this is only a fraction of it in the photo. I gave thanks that my dad was not on that wall. Think of how those families feel. I found myself sending them my love and sharing their pain.

A Frenchman who works for superindendents drove me back to town, to the car rental office. With me I took two little American flags and a packet of information about the American cemeteries in Europe. Alan was already off showing another American family the grave of their relative--and I knew they were in the best of hands.

##

Home

Next

# posted by bevjackson @ 8:20 AM